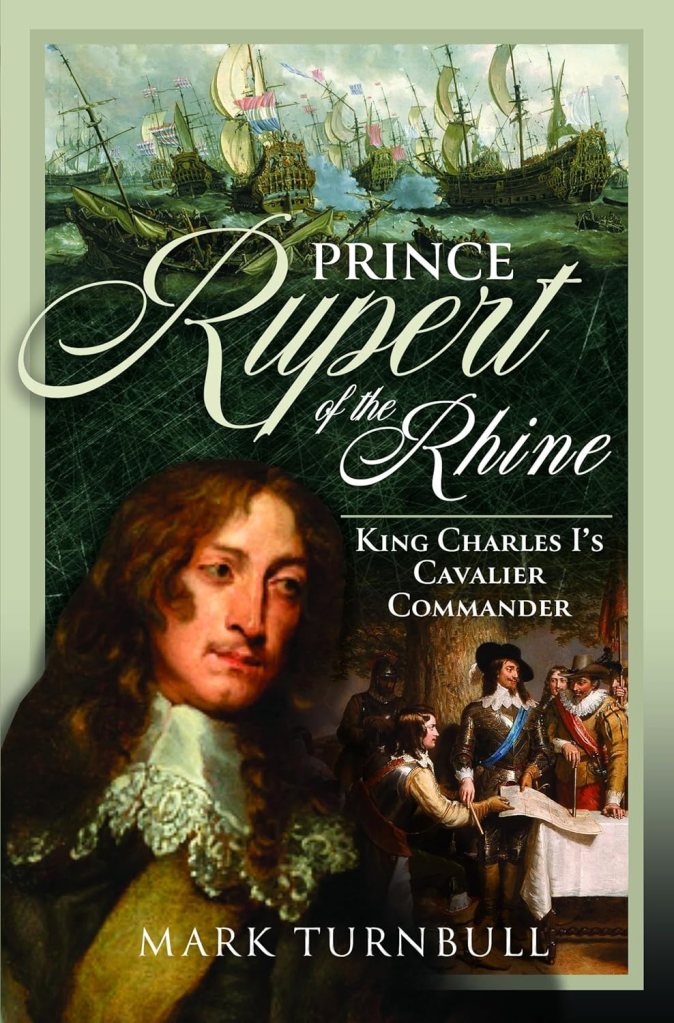

My review of Prince Rupert of the Rhine – King Charles I’s Cavalier Commander, a new biography of Prince Rupert of the Rhine by Mark Turnbull.

Any biography of a major seventeenth-century figure that receives praise from two such giants in the field as Professor Ronald Hutton and Professor Nadine Akkerman has to be something a bit special.

Prince Rupert has always been a divisive individual. Even on the day he was born, half the Bohemian Estates wanted to vote him as heir to their throne, and half didn’t.

He reached the apogee of his fame during the First English Civil War, when he was seen as an inspiring hero by those who supported his uncle, King Charles I, and was cast as a vile, possibly demonic, foreign mercenary by his enemies. Which was rather ironic. In that most religiously motivated of wars, Rupert’s strong Calvinist faith (something he had been so staunch in that he had endured years as a prisoner of war rather than abandon it) was much closer to the creed Parliament professed than his uncle’s Laudism.

For a generation, the image of Rupert as Timothy Dalton with a lap dog tucked up on his saddle in the film ‘Cromwell’ influenced how the prince was perceived. But just as Cromwell was not one of the five MPs the king tried to arrest, as that film falsely claimed, so Rupert was not a pretentious fop, and Boye was not a small ball of fluff but a full-sized and highly trained hunting dog.

Today, there are those who are Rupert’s unstinting admirers, and there are those who like to cast him as no better than an aristocratic thug. The heat of emotion on both sides tends to obscure the reality and leaves us with the same two-dimensional hero or villain stereotype he was depicted as during those brutal and divisive wars. And of course, the truth is nothing like that simple. Just as much as any other human being, Rupert was complex and deserves better than to be pigeon-holed in one box or another.

Beginning with Rupert’s birth in Prague, at the epicentre of events which exploded into the Thirty Years’ War, this biography takes the reader through what is known of the prince’s education as one of a large and growing family of children born to the exiled Elector Palatine and his wife, the Winter King and Queen. For half a decade, his mother was heir to the English throne, and she held the devotion of many Englishmen who saw her cause as their own. A devotion which made them demand that King Charles support her cause. But they were not quite devoted enough to vote the kind of money that support required on an ongoing basis, whilst at the same time chastising the king volubly for failing to do so.

Elizabeth of Bohemia with all her children living and dead. Prince Rupert is shown directly behind his mother.

Of necessity as well as inclination, Rupert was raised to be a soldier, and Mark Turnbull looks at new evidence of how the prince developed his skills as a military commander and the consequences of that. He was fighting in his family’s cause from his teens. So, even despite their religious differences, it is not surprising that he was quick to support his uncle when the English Parliament declared war against him and raised an army to try and force the king to their will. Indeed, had it not been for Rupert, there might not have been an adequate military response in time.

His deeds of daring – or despoilation, depending on the perspective taken – in the First English Civil War are well known, but the biography brings some new insights to this part of Rupert’s life, especially around his conduct of the Battle of Marston Moor and his relationship with the king. What is much less well known is that after the king’s defeat, Rupert took to the seas and for some years became pretty much a pirate working for the Royalist cause.

After the Restoration, Rupert was a major figure in the court of Charles II, involving himself in culture, art, science and trade as well as continuing his military role as a naval commander. But it is this last phase of Rupert’s life, so often seen as almost irrelevant compared to his early fame, that this biography illuminates particularly well, and adds to through looking closely at the women he shared his life with. We are shown Rupert as a family man, which is something usually glossed over and diminished. His chosen life partner is generally cast as a mere mistress, as if she were no one of any real significance in his life, when in truth, his devotion to her and their daughter was central to who he was in his later years.

It has been almost twenty years since there has been a new biography of the prince, so in many ways this is a long overdue reappraisal of his life. As well as including the latest published research, Mark Turnbull has gone back to the archives and looked with fresh eyes at the documents available, and even decoded some letters for probably the first time. He also brings a modern approach to the biography, seeing Prince Rupert in the round, significant for being a man of his time rather than just for his impact on events. So, as well as showing the familiar Rupert striding out on the stage of history, this book also explores the private man, his personal relationships with family and friends, and the women with whom he was intimate.

This is not a hagiography of the warrior prince; this is – as Professor Akkerman says – ‘a fresh and balanced’ approach to the life of a man who even today gathers both ardent supporters and passionate detractors.

There have been several excellent modern biographies of Prince Rupert, mostly highlighting his career as a commander on land and at sea: Morrah, Thompson, Kitson, Spencer – I’ve read them all, and they paint a collective portrait of the prince which fits very well with the formal paintings we have of him. In this new biography, Mark Turnbull does that too, but he does something else as well. He shows us the prince as a man, with all the strengths and weaknesses of the human condition, with family, friends and lovers, with principles, passions, hopes and regrets. And that is something quite remarkable.

Prince Rupert of the Rhine – King Charles I’s Cavalier Commander is available to purchase directly from the publisher, Pen and Sword, and from other retailers, including Amazon.

After a visit to Helmsley Castle at the age of 10, Mark Turnbull bought a pack of ‘top trump’ cards featuring the monarchs of England. The card portraying King Charles I fascinated him. Van Dyck’s regal portrait of the King and the fact that he was executed by his own people were the beginnings of Mark’s passionate interest in the English Civil War that has lasted ever since.

He thoroughly enjoys bringing this period to life through writing, having written articles for magazines, local newspapers and online educational sites, and used to re-enact battles with The Sealed Knot.

Mark is an Associate Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. He also produces a War of the Three Kingdoms podcast called ‘CavalierCast – The Civil War in Words’. This was the first (and is the longest running) podcast solely dedicated to the civil wars. It explores a variety of topics with leading historians and authors. He is also the author of another biography, Charles I’s Private Life and The Rebellion Series, historical fiction set in the civil wars.

He is one of the co-founders (with Dr Erica Canela and Andrea Zuvich) of the Stuart History Festival, the world’s first-ever festival dedicated to Stuart history.

You can follow Mark on X(Twitter) and Facebook.