It is always a challenge when writing historical fiction, to make it clear where the author has placed smudgy pawprints over historical events to make their story, and where they have drawn on the known historical record.

For example, Frances Villiers did indeed have a secret illegitimate child at this time and Kate’s experiences at court include verifiable historical details such as the masque performed that year, the troops being raised and the doubts about their purpose, the narrow escape from drowning Mansfeld endured, the presence of Christian of Brunswick, and many other details which a scholar of the period would recognise, whilst no doubt tutting at my character dancing through them. Even the unlikely named Hanging Sword Alley was (and is) a real location in London, and was known for having a fencing school, although, alas, not one run by Venturo di Zorzi.

National Trust Wikimedia Commons

Equally, whilst Captain Vroomen and his crew are most decidedly not historical individuals, they represent a group of people who did exist. The Dunkirkers were originally a Spanish naval fleet based in the port, but to this was added a growing, privately funded, flotilla of licensed privateers. Although they began operations in the 16th century in support of the Spanish fight against their rebellious Dutch provinces known as the Eighty Years War, it was only after the end of the Twelve Years Truce in 1621, that they reached their full power. Then, for over two decades, despite all attempts to blockade them in their home port, the Dunkirkers devastated Dutch merchant shipping and that of their English allies. They may even be credited as a cause of the First English Civil War since it was mostly to counter their threat that the infamous Ship Money had to be raised.

This surge of piratical success was due to the development of a new type of ship by the shipwrights of Dunkirk: the fragata. It had a more slender and lower profile, and was smaller than other warships of the time. It also had the advantage of carrying oars as well as sails. These could be deployed for manoeuvring or to gain the advantage when there was little, or an opposing, wind. Tragically, no painting or design sketch remains to us of what these vessels, the forerunner of the frigate class of warships, actually looked like, so I have had to employ an educated imagination to describe Star of the Sea.

Museo del Prado Wikimedia Commons

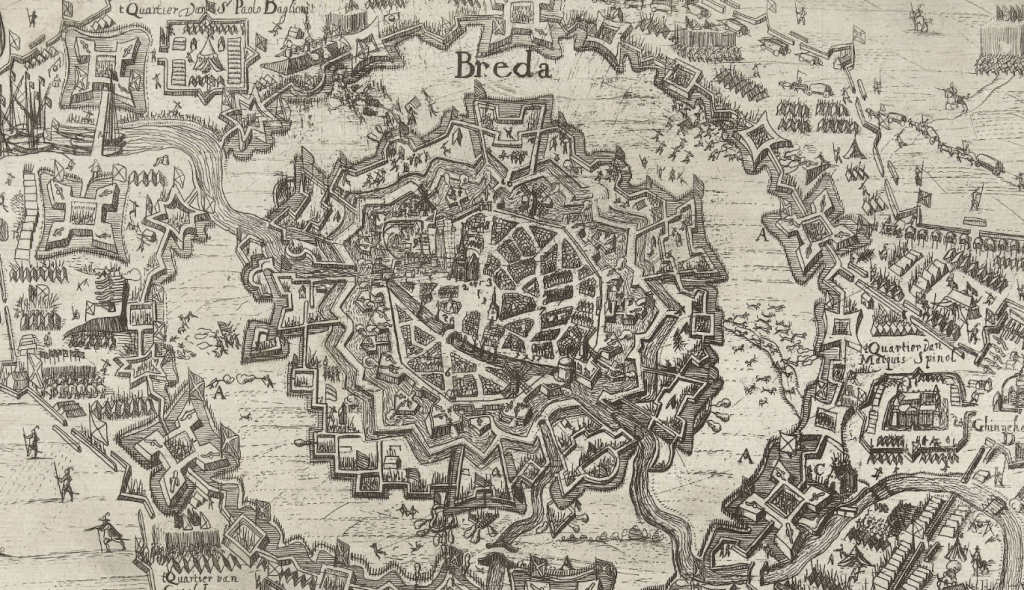

Today the 1624 Siege of Breda is best known to us from this painting ‘The Surrender of Breda’ by Diego Velázquez. This shows Justin of Nassau bending knee before a very gracious Ambrogio Spinola, Marquess of Los Balbases. But at the time it was best known for the sheer scale of the thing.

Breda was superbly defended by its extensive fortifications and the waterways about it. By the expectations of the time no siege could endure long enough or be made close enough to force a capitulation. But Spinola organised the investment of the city with patience and skill. He mustered a huge besieging force of around 80000 men, who both besieged the city and manned and protected the network of supply lines needed to maintain it running back deep into the Spanish Netherlands. The city eventually surrendered after nine months as the copious supplies they had stored finally ran out and all attempts at relief had failed. It is also true that whilst those supplies included many luxuries, no one had thought to stockpile tobacco. In the opening months of the siege, before it became a tight noose about the city, tobacco smugglers would make the hazardous passage in and make a very good profit from doing so, provided they evaded capture.

It shows Breda’s own defences and the complex siege works built to surround it.

It is also worth mentioning that the tale of the city being captured from the Spanish before (in 1590) by Dutch soldiers sneaking in on a peat barge, as Jorrit and his friend Seppe played out, is also true. The barge was kept on display until the Spanish destroyed it when they retook the city. A small piece of the barge was saved and is, I believe, on display in the Stedelijk Museum in Breda.

Finally a word about alum. Used for many purposes from medicine to metallurgy, from papermaking to fixing bright coloured dyes, to even being an essential ingredient of the Philosopher’s Stone, alum had always been a prized resource. But in the days before it could be synthesised, it was also a scarce one with few known deposits. Weight for weight it was almost as valuable as gold. The main supplier to Europe at this time was the Pope as alum had been mined in Papal lands since the 15th century (incidentally making the papacy incredibly rich on the proceeds). When Henry VIII broke with Rome he also lost ready access to alum for his subjects.

Then Thomas Chaloner, a Yorkshireman who had travelled all around Europe, noticed the similarity between some aspects of his land, the rocks and plants that grew there, and those of Tolfa where the alum was mined. James I granted a monopoly patent to Chaloner and a consortium including Sir Arthur Ingram in 1607. But the process of alum production being a closely guarded secret it was difficult to get men with the skill and knowledge needed. As a result, for many years the monopoly lost money. As production began to pick up, Whitby grew. From being a whaling and fishing port, it expanded rapidly to become an industrial one. In October 1624 Sir Arthur Ingram, who was by then controlling the monopoly, was arrested for financial irregularities and accused of mistreatment of his workers. He was stripped of the monopoly the following February. But alum production on the Yorkshire coast went from strength to strength and brought great prosperity to Whitby over the next 200 years.