Historical Background to The Physician’s Fate

The battles of Piercebridge and Tadcaster took place pretty much as I describe in the book. Although I did take one liberty. There is, to the best of my knowledge, no indication John Hotham damaged the bridge in the first engagement in the manner I describe, something which will undoubtedly upset purists. However, Fairfax certainly holed the bridge at Tadcaster.

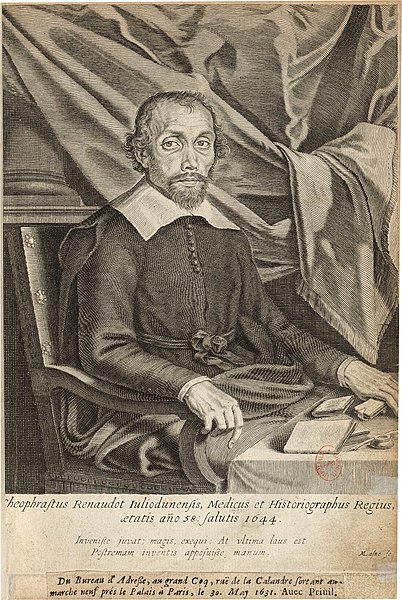

Linda Spashett, Storye book, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Théophraste Renaudot was Commissioner General of the Poor in Paris. His headquarters was the Bureau D’Adresses, established at the Sign of the Cock on the corner of the Rue Calandre and Rue du Marché-Neuf on the Île de la Cité. He was a force of nature who as well as running the Bureau as a pawnshop, employment agency, clinic and dispensary for the poor, also held weekly debates on issues of scientific and philosophical interest and published their proceedings. These he stopped as soon as Richelieu died as he was already under pressure for them with murmurs of heresy. In addition, Renaudot might have a good claim to be the creator of the modern newspaper as his La Gazette de France, which he began in 1631, contained news, editorials and advertisement and was printed weekly.

Sadly, he met much opposition for his good works. In particular from the Faculty of Medicine in Paris which disapproved both of his methods of medical practice and of his freely dispensing of them to the poor. Within a year of the death of Cardinal Richelieu, the Faculty that Renaudot had fought so hard against, succeeded in banning him from medical practice. At their instigation the parlement of Paris forced him to close his Bureau and end all the services it had offered to the poor of Paris. He remained the editor of La Gazette, however, and in 1646 Mazarin appointed him Historiographer Royal (the official court historian) to Louis XIV. La Gazette continued to be published even after his death in 1653, covering the French Revolution in the late Eighteenth Century and surviving in one form or another until 1917.

The ambassador for King Charles to the French court in Paris from 1641-1660 was Richard Browne and he maintained an Anglican chapel in his house. His daughter, Mary, was married to the diarist John Evelyn in 1647, when she was just twelve years old. Evelyn and Browne became friends after they met in 1643, an event recorded at the end of the entry in Evelyn’s dairy for Monday 16 November 1643:

We lay at Paris at the Ville de Venice; where, after I had something refreshed, I went to visit Sir Richard Browne, his Majesty’s Resident with the French king.

Browne impoverished himself in the king’s cause and was rewarded with a baronetcy by Charles II in 1649.

Duchesse d’Aiguillon

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Marie Madeleine de Vignerot du Pont de Courlay, Duchesse d’Aiguillon was the daughter of Richelieu’s sister. After a brief marriage in 1620 (her husband died in 1622) she became, through her uncle’s influence, the lady in waiting to Marie de Medici until her fall from grace. Usually that was an honour reserved for the highest of nobility and it placed Marie Madeleine in control of the wardrobe and immediate household of the king’s mother. In 1638 Richelieu had her created Duchesse d’Aiguillon in her own right. After her uncle’s death she retired from court and concentrated on her charitable works. She never had a companion/maid Geneviève Tasse, who is purely my invention.

Making Science Social: The Conferences of Théophraste Renaudot, 1633–1642 by Kathleen Wellman.

City on the Seine: Paris in the Time of Richelieu and Louis XIV, 1614-1715 by Andrew Trout.