Although there is a popular perception when it comes to witchcraft in the first half of the 17th century in England, that credulity ran higher than rationality, the evidence suggests otherwise.

There were undoubtedly times that belief was high, especially in the trauma of civil war when Matthew Hopkins, the infamous witchfinder general was doing his work. The power that such belief in witchcraft held over people’s minds and the terrible consequences of that belief are explored in The Mercenary’s Blade. But, whilst there were those then, as now, willing to believe in such things, there were many who were less inclined to do so.

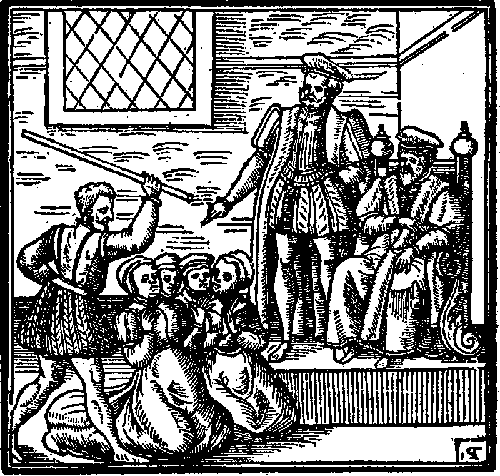

In 1597 King James VI of Scotland decided to publish his book Daemonologie in which two characters, Philomathes and Epistemon, argue over whether or not witches even exist. The sceptical Philomathes is eventually persuaded by Epistemon that ‘that witchcraft, and Witches haue bene, and are, the former part is clearelie proved by the Scriptures, and the last by dailie experience and confessions.’ Epistemon sets out his case, calling upon Biblical authority and examples from history, touching upon tales of ‘Pharie’ and which aspects of astrology are legal and which are not.

Aside from offering an intriguing glimpse into the mindset of King James, who of course became King of England a few years later, it is a reminder of the power belief in witches could have throughout society. And a huge red flag regarding the assumption of the universality of such belief as well.

James says in his preface that he wrote the book to ‘to resolue the doubting harts of many’ and Philomathes says that the existence of witches and witchcraft is something: ‘but thereof the Doctours doubtes’.

In other words, far from there being a strong belief throughout Scottish society that these things were true, a major reason James felt the need to write his book was that the level of scepticism about the existence of witches and witchcraft was held by the ‘harts of many’ to be very much in ‘doubtes’.

In Scotland, James oversaw an increase in the persecution of people, usually women, for witchcraft. But James himself, whilst adamant that witches did exist, was not blind to the malicious use of accusations. In the later years of his reign, he became more aligned perhaps with Philomathes, who, whilst not doubting the existence of the devil and sorcery, was less sure that there was so much truth in every individual accusation of witchcraft.

The case of William Perry of Bilston, is a good example.

We know of his case from a published pamphlet of anti-Catholic rhetoric published in 1622. Following an exposition upon how deceptive Catholic Priests can be, there is a brief account that the author, Richard Baddeley, attributes to a Mr Wheeler, which is presented as a confession made by a Catholic priest. This is followed by an account that is said to have been taken from court hearings.

The story begins with thirteen-year-old William Perry suffering convulsions and blaming a woman for his attacks. When she was brought into his presence he started vomiting straw, pins and rags which led to her being arrested and condemned as a witch. However even with Ms Clarke safely behind bars and awaiting execution, young William showed no sign of any improvement and people would visit his troubled parents to witness his attacks and leave gifts for them. Since his parents were people of no great means, his father is described as being a husbandman, so probably a farm labourer, such gifts were much appreciated.

Local clergymen tried to calm him by reading from the Bible and whenever the first verse of John was read to him he would go into contortions and start vomiting odd items.

By now the case had been brought to the attention of the local bishop of Lichfield and Coventry, who the pamphlet refers to as Thomas L. That would have been Bishop Thomas Morton, who would go on to become Bishop of Durham.

The bishop read the Bible to the boy in Greek. This time there was no reaction to the verse, which convinced the bishop that William was not genuinely possessed. A demon, the bishop reasoned, would know Greek.

Torture failed to get the boy to confess, so he took William to his castle and had him watched. But the symptoms of possession continued, including William’s urine being black, Eventually, believing himself unobserved, the boy was seen to take an inkhorn from beneath his mattress and pour ink into his chamberpot. Challenged with this, William finally confessed not only to having been a fraud, but to having been persuaded into it and taught the necessary tricks by a Jesuit priest.

The tale has a happy ending with William Perry asking forgiveness when brought to trial at the assizes.

…the Boy craued pardon first of Almighty God, then desired the Woman there also present, to forgiue him; and lastly, requested the whole Countrey, whom hee had so notoriously and wickedly scandalized, to admit of that his so hearty Confession, for their satisfaction.

I am amazed at how often this story is quoted, uncritically, as being true when there is, to the best of my knowledge, no other contemporary reference to it anywhere else except in this pamphlet. One could poke many holes in it, not least why William, held in custody and closely observed, would not have been thoroughly searched.

But be it true or merely anti-Catholic propaganda, the story still makes the excellent point that belief in witchcraft cases as often being fraudulent was rife. The very fact that such a story could be used for such a purpose shows people were open to accepting fraudulent witches as possible.

And true or not it would have gathered impetus and been widely believed, adding to the general feeling that not all witchcraft accusations were valid ones.

In 1634 science stepped in.

Back in 1612 witch trials had taken place in Pendle in Lancashire and nine people were hanged as a result. Years later a related trial came to court with seventeen women accused. This time, although they were found guilty, four of them were brought to London with the king’s approval, to be examined by physicians, midwives and surgeons, led by Sir William Harvey the Royal Physician.

After examining the women Harvey declared he and his team could find no evidence of these women being witches and they were pardoned.

After that witchcraft cases were vanishingly rare in England. Until, in a nation ripped apart by the chaos and uncertainty of civil strife, and against a backcloth of war and brutality, Matthew Hopkins began his personal crusade as the self-appointed Witchfinder General.

(The first image is Suspected witches kneeling before King James, a plate from Daemonologie by King James, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)