Jane Fromond is a fascinating figure in history.

We know intimate things about her that we know about no other woman of the era. Scholarly scientific analysis has been made of the record we have about the timing of her periods, which her husband, Dr John Dee, recorded in his diary (he was seeking to know if conception was more accurate than birth in astrological calculations). He also often recorded when they made love. Sometimes he seemed to regard her much as he might any of his experiments.

But that he had great affection for her and she for him is very clear and shines through even the coldly dispassionate lens of his private diary.

Jane was probably born and raised in East Cheam in Surrey, not far from Mortlake where John Dee lived. Her mother was Elizabeth Mynn, and Jane’s given name was that of her grandmother on her mother’s side. Her father was Bartholomew Fromond, who was from the armigerous gentry, their coat of arms blazoned as Per chevron ermine and gules, a chevron between three fleurs-de-lys, Or. Jane was part of a large family. According to the Clarenceux king of arms County Visitation of 1572, she was one of eleven children—five boys and six girls—of which she was the fourth daughter.

Both her parents (but especially her mother), as members of the gentry and living not far from London, would have had contacts at court. That was no doubt how Jane found a place in the service of Elizabeth Fitzgerald, Lady Clinton, known for her beauty as ‘The Fair Geraldine’. Lady Clinton was one of Queen Elizabeth’s ladies and reputedly a personal friend of the queen.

National Gallery of Ireland – Wikimedia Commons

Jane likely entered Lady Clinton’s service around the same time as her new mistress became a countess with her husband’s elevation to the Earldom of Lincoln. We can assume Jane navigated the dangerous corridors on the outskirts of courtly power with adequate skill, because more than once after her marriage, she was able to return there to appeal to her contacts at court for assistance on behalf of her husband.

We have no record of how John and Jane met, nor whether there was mutual affection between them before they married or if it was simply an arranged marriage. It was said to be against her father’s wishes, so perhaps there was more than pragmatism to the match. John had recently been bereaved of his second wife, about whom we know nothing at all, not even her name. Whilst she was no great lady, Jane would have brought to the marriage her connections of family and friendship within court circles. These would have been of value to John who, despite his informal role as the queen’s philosopher, was always struggling to gain a formal place and position there.

At the time they married Jane was twenty-three and John was fifty-one. In an era where the hazards of childbirth, accident, war and illness meant many remarried—and not uncommonly more than once—such large age-gap marriages were not regarded quite as we might think of them today. To the Tudor mind, it was a good thing that the groom was a well-established older man as that meant he could offer his bride a secure life. For John, Jane’s youth would have been important as, despite being twice married already, he had yet to start a family.

So Jane Fromond became Jane Dee and the mistress and manager of ‘the Mortlake Hospital for Wandering Philosophers’ as John once referred to his house in a petition to the queen.

It must have been a huge challenge even for a capable woman like Jane who would have been trained from birth in the skills required to undertake the task of running a substantial household. But unlike most wives of gentlemen who took on a purely domestic responsibility, Jane had to oversee the smooth running of what was also her husband’s workplace.

We only know Jane through the eyes of her husband, but it is clear he found her efficient at her job as mistress of the Mortlake house. It was Jane who ensured adequate provisions were kept ready and tradesmen were employed at need. She managed the household finances and the domestic servants—cooks, housemaids, nursemaids, governesses, gardeners, manservants. It was Jane who saw to the needs of her husband’s live-in apprentices and his employees—such as Roger Cook, his alchemical assistant, and eventually Edward Kelley, John’s scryer.

Jane was also required to be the perfect hostess to Dee’s many guests, some of whom were men of great social standing. Guests who might come to consult his famous library and stay for a night or two, perhaps with little or no warning. The Dees’ house being on a readily accessible main road just outside London and close to the Mortlake landing on the River Thames, and John having the reputation he did as a scholar, philosopher and astrologer, there was pretty much an endless stream of visitors from all ranks of society.

Jane was the one who had to manage those guests.

British Museum – photo Wikimedia Commons

But that meant more complex provision than any regular hostess needed. She was fully aware of the sensitive nature of her husband’s work and how perceptions of it could threaten the safety of their household. Anyone walking into his private rooms and seeing an oddly made table, inscribed with strange letters and symbols, with a scrying stone upon it was likely to draw conclusions and might add to the dark rumours of his being a conjurer.

After a couple of mishaps, they evolved a system to try and avoid such embarrassing incidents.

The room in which John did his work had double doors fitted. If he was available he would leave one open—presumably ajar. It was not always effective as John sometimes forgot to close the doors properly before beginning his communications with angels, not to mention that Jane saw no reason why a closed door should mean she could not open it to inform her husband his dinner was ready even if he was chatting with angels!

However Jane was not permitted within that workspace itself. At one point when she was clearly at her wits end trying to make the family finances meet the requisite expenditures, she asked if the angels might be consulted on her account. She petitioned them to make ‘sufficient and needful provision’ for the household so they were not reduced to selling ‘the ornaments of our house and the coverings of our bodies’.

She received a short shrift from the angels.

They told Jane she was forbidden to enter the ‘Synagogue’—referring to the room where Dee talked to the angels—and to get back to her housework: ‘sweep your houses’ they told her.

It is perhaps not surprising that John recorded in his diary quite a few occasions when Jane lost her temper.

However, it is worth noting that the man who told her this message from the angels was none other than the aforementioned Edward Kelley, a man who her husband had observed she disliked and distrusted from the first time she met him. To John he was an essential part of the household because Kelley alone had the ability to see and hear the angels John was so desperate to communicate with.

Photographer: DickDaytona via Wikimedia Commons

The antipathy between Jane and Kelley grew worse after Kelley married Joanna Cooper, a young woman from Chipping Norton. It is possible Johanna was a friend of Jane’s, or some have suggested Kelley was paid to marry her to legitimise a nobleman’s offspring. Effectively a servant living in another man’s house, Kelley was hardly a great catch, but for a woman alone with two very young children in that era, he might have been the only alternative to an impoverished, possibly disgraced, future for herself and her children.

The two women soon became friends if they had not been so before. In the frequent rows Kelley had with his wife, Jane always backed Joanna. At one point Kelly told John: ‘I cannot abide my wife, I love her not, nay I abhor her; and here in the house I am misliked, because I favour her no better.’ His words hint at Jane’s dislike for him.

Soon after the Kelleys’ marriage, John began getting apocalyptic messages from the angels, saying things like: ‘The second coming is not long unto’. He was persuaded that he should leave England by Olbracht Łaski, a Polish nobleman who was famous for his spectacular beard. Łaski was a nasty piece of work. He had once attempted to seize the Polish throne for himself squandering his first wife’s wealth. When she died he had married another wealthy woman twenty years his senior, persuaded her to sign her lands over to him and then kept her a prisoner in close confinement and poverty whilst he remarried (bigamously) yet again. Łaski’s real mission in England was to secure Dee’s service as an alchemist to make gold for the Polish king and thus to resecure that king’s favour. Speaking through Kelley, the angels predicted great things for Łaski—including that he would be king of Poland or Moldavia within the year (spoiler: he wasn’t). So when Łaski ran out of money again and had to flee England to escape his debts John Dee went too. He left the Mortlake house in the care of his brother-in-law and took his wife and family with him.

Away from Mortlake and compelled to travel across Europe, Jane’s organisational and financial skills were tested to their limits. She was pregnant and had two young children with her, as well as Joanne and her two young children to look after, together with their servants and baggage. At times Jane was left to manage it all alone whilst John and Kelley travelled on to meet with various important individuals. She had to endure the rigours and hazards of travel and learn how to make each stop-over accommodation, be it for a few days or a few months, into a home for her family.

Over this time her dislike of Kelley intensified and Kelley himself became ever more erratic. He even got into fights in the street. The advice he gave John from the angels always promised great things were coming. In reality, following the guidance he got through Kelley, Dee was received with at best polite refusal and at worst threats and even banishment by the great rulers he tried to get to take an interest in his work.

It must have been a bit of a relief to Jane when, after three years of travelling and temporary dwellings, they were granted a house in Třeboň. Given to them by Vilém z Rožmberka, Lord Rožmberk, the High Burgrave of Bohemia, who was close to Emperor Rudolf. It was to be home to the Dees and the Kelleys for two and a half years.

As she settled into Třeboň, a beautiful town surrounded by fishponds and orchards, Jane must surely have been quietly delighted to have a house she could consider her own to manage as she wished again, and an end to the remorseless rigours of travel. Perhaps she imagined things would finally be stable and she could raise her family in peace. John and Kelley would get on with their work under the protection of Lord Rožmberk and she and Joanna and their children would live much as they had in Mortlake.

If so she would be cruelly disappointed. That house was to be the setting for the hardest challenge of Jane’s life. A challenge that would call into question all she believed, threaten everything she cared about, and leave them all profoundly changed…

Those disturbing events in Třeboň form the basis of the story that I tell in A Pact Fulfilled, my contribution in To Wear a Heart So White, an anthology of short stories about crime and punishment published by the Historical Writers Forum.

It is my tribute to the fortitude, resilience and strength of an amazing woman who had to live with demands and expectations few others in her times had placed upon them.

A Pact Fulfilled was long listed for the Dorothy Dunnett Society/Historical Writers Association Short Story Competition in 2023, Dorothy Dunnett’s centenary year.

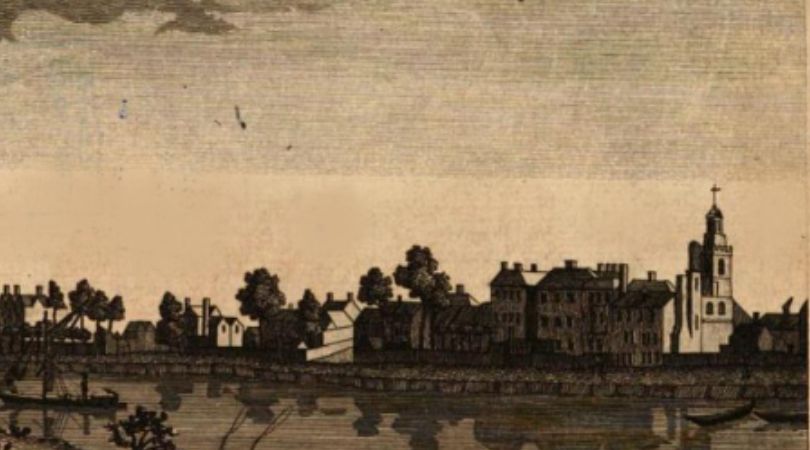

The title picture (also shown below) is a detail from: View of Mortlake from the River. A copperplate engraving from A New and Universal History, Description and Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, the Borough of Southwark, and their Adjacent Parts… by Walter Harrison (1775) Source: Google Books.

Although this was created nearly two centuries later, some of the buildings we can see between the church and the river might once have been part of the (by then closed) tapestry works which had previously been the Dees’ Mortlake Hospital for Wandering Philosophers…

To be sure not to miss out on news about my current projects, you can sign up for my newsletter here and receive a free Lord’s Legacy short story.

An apt and compelling tribute to Jane, whom I wholeheartedly admire after reading her story.

LikeLike