Paula Lofting has a new book out Searching for the Last Anglo-Saxon King, Harold Godwinson, England’s Golden Warrior. I always find it fascinating to see the similarities there can be between eras and asked her some questions about the ways in which events in 11th Century England can be compared (and contrasted) with those in the 17th century, and Harold can be compared with Charles I.

***************************************

I know very little about the Anglo-Saxon Era and the Norman Conquest, except what every schoolchild learns about it, but it strikes me there are a number of points where it has some interesting congruence with the First English Civil War. As Tostig was Harold’s brother, were there aspects of Harold’s fight for the crown which were in a sense a civil war or was it entirely about fighting foreign invaders?

So, there’s no real evidence that Harold had his eye on the crown until January 1066 when Edward died, and he was suddenly proclaimed king. Here is a brief potted history of what led to his ascendancy to the crown:

– August 1065 – Tostig rules as Earl in the north. The leading chieftains decide they have had enough of his rule. They claimed he had committed crimes against them. They marched on his HQ in York where they killed 200 of his huscarls. Luckily for Tostig, he was in the south with the king, hunting.

– The protest didn’t end there. The rebels wanted to oust Tostig and replace him with the younger brother of Earl Edwin of Mercia, Morcar. Both these young men were the sons of the deceased Alfgar, who was a rival of the Godwinsons.

– The Northumbrians and Yorkshiremen called Morcar to them, and they planned to head south to Tostig’s lands in Northampton gathering an army through the lands of shires on the way, meeting up with Edwin, Morcar’s brother at Northampton, bringing his Mercians and also a large number of Welshmen too.

– When word got through to Tostig and the king what was going on, Tostig demanded that Harold go to parley with them and sort out the mess, but the leaders of the rebel army refused to compromise. They were adamant that Tostig needed to go because of the charges against him and wanted the king to gird Morcar as their earl.

– Harold was in a difficult position. As second to no one but the king, his job was to do the king’s bidding, and the king wanted him to use force to reinstate Tostig. Harold was faced with choosing between creating a civil war or betraying his brother and going against his king. If he chose civil war, there would be enormous bloodshed between which the south had no stomach for anyway, and if he chose to accept the conditions laid out by the rebels, he risked losing the respect of the court, his family, the king and his brother. He chose to put the country before his king and blood.

– The king was backed into a corner and had to agree to the rebel’s demands. It was unlikely that the leading thegns, in the south wanted to go to war with the north anyway, so this also added to Harold’s dilemma. In any case, civil war would have only served to leave England open to invasion. Whilst the king was thinking with his heart, Harold was thinking with his brain and the preservation of his country, and the safety of his people was more important.

–Tostig and his wife had to leave and went into exile in Flanders, to her brother who gave them refuge. Tostig got himself together with the King of Norway, Harald Hardrada, to set the Norwegian king on the English throne. Bent on revenge, he set about planning his invasion with his ally.

– Sadly for Tostig, Harold was to defeat him at Stamford Bridge and his hopes of reinstatement in England as Hardrada’s deputy were wiped out in one day’s battle. Both men were killed by the English forces.

So you see, it was not civil war that tore the brothers apart but their inability to work together on this crisis. Tostig accused Harold of orchestrating his downfall, however I don’t believe that was the case. I think there may have been jealousy between them which had festered. After all, they had worked together very well after their successful invasion of Wales in 1063. Something had possibly gone wrong between them, but it is difficult to know, but there is evidence that they had become rivals. The mysterious destruction of the hunting lodge Harold was building for King Edward may have played a part in their schism.

I notice that Charles I was descended from Harold. Harold’s grandson (through his daughter, Gytha) was Mstislav I, Grand Prince of Kiev and by separate lines of descent, Mstilav was an ancestor to both James I and Anna of Denmark. So I was wondering how important was descent in legitimising kingship in Anglo-Saxon culture?

John Speed’s Saxon Heptarchy map, from his Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain, 1611 – via Wikimedia

It was generally believed that if you were the son of a king from the line of Cerdic of Wessex, you were entitled to be addressed as ætheling, meaning of the noble family, therefore one would be ‘throneworthy’. This did not necessarily mean that the eldest son would automatically take the throne. It was the king’s privilege to nominate his designated heir, but ultimately it was down to the witan (the king’s council) to cast their vote as to who they would accept as king. So we might have a situation where the king nominates his eldest son from his first marriage, but a rival faction might support a younger son from his second marriage or, as in the case of Cnut, a son from an unofficial marriage. It would be up to the witan, to choose who they believed was the strongest candidate who would lead the country well.

In Harold’s case, having no known connection to the House of Wessex, but his status as sub regulas (underking) overrode the claim of young Ætheling Edgar due to his seniority, strength, and power.

Thinking of kingship, in 17th-century England, the notion of Divine Right had evolved. This was the idea that God had chosen and appointed the king and given him full authority to rule. This was not a licence to do what he wanted, but a responsibility for the well-being of his kingdom and its people, for which he would be held to account by God. Is this at all similar to the concept of his kingship that Harold held?

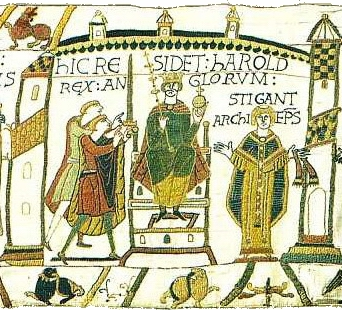

From the Bayeux Tapestry via Wikimedia

I would say definitely, kings were crowned and anointed with holy oil from the days of Edgar, who was the first to be referred to as King of England. This was taken from the bible as many kings or chosen prophets were anointed with oil recognising their divine appointment from God. As with the 17th century, the early English kings were not given licence to do as they pleased. They had to rule with the permission of the witan but had ultimate authority to make decisions that affected the kingdom. He was responsible for the safety and security of his kingdom, and I suspect he knew that it was his duty to be accountable to God for his governance of the realm.

Harold did his best to see to the safety of the kingdom, and even as earl of Wessex, he was given the authority to make decisions on Edward’s behalf, being sub regulas and dux Anglorum. These gave him the ability to make both kingly and military decisions.

During his short reign, Harold was to spend it securing England’s shores with naval and military might. He had to ally himself with the difficult northerners by marrying the sister of Edwin and Morcar. He then had to march north at lightning speed to fight the might of his brother and Hardrada then did the same back south to face William of Normandy.

Harold took his duties seriously. Because the Normans were assaulting his lands, burning homesteads, and killing his people, he refused to let his brother, Gyrth, fight on his behalf whilst he waited for the rest of the fyrd to catch up in London. He was angry and infuriated at what was happening in Sussex and he marched with less than his army than he could have had to face William to stop the invaders in their tracks.

Unfortunately, his efforts were in vain.

Charles I was in conflict with his parliament long before the outbreak of civil war. What was the nature of the ‘parliament’ Harold had to contend with, and what kind of issues did they cause him?

Old English Hexateuch, from the Cotton library at the British Museum via Wikimedia

The parliament was the Witanegemót, the meeting of wise men, which was made up of nobles, earls, archbishops and bishops and other important people. The function of the body of the Witan was to advise the king, assist with law-making. As said previously the king had the ultimate power so didn’t have to act on what the witan suggested, however in Edward’s case he was often given little choice as the earls in the 11thc had great power and were able to overpower Edward’s decision, as we see when he wanted Harold to gather the southern fyrd to force the north into obeying his command to reinstate Tostig Godwinson in his position as earl of Northumbria.

When Edward died, he appeared to have most of the witan supporting him into the kingship. However not all of the earls had given their oaths. Edwin and Morcar, who ran the northern parts of England, had left court before giving their fealty to their new king. After Harold had his coronation, and had seen to some admin and the security of his shores in case William was to invade, he set off up north to York to treat with the young earls and in return for their support, he married their sister Aldith as previously mentioned.

Yorkshire is a place that held great significance to the fortunes of both kings. For Harold it was winning a battle there, at Stamford Bridge to defeat his brother Tostig and the invading Harald Hardrada. For Charles I, although very much a place of strength early in the war, it became the site of the first major defeat for his cause at Marston Moor, a loss that ultimately led to the greater defeat at Naseby the following year. Do you think Harold’s Yorkshire victory contributed to his defeat at Hastings?

It definitely had a part to play in Harold’s well-being. It was a stressful time. The relationship between himself and his brother was fractured, which may have affected his relationship with his sister, the queen and the king, for they were excruciatingly fond of Tosti. He’d had to bring north and south together by entering into a marriage he may not have really wanted. He already had a wife, Eadgifu – also known as Edith – Swanneck. She was his more Danico wife, a type of marriage that was not blessed by the church, but legitimate in the eyes of the law, nonetheless. Harold may have always known that one day he might have to ally himself in order to keep peace in the land, but he had evaded it for more than twenty years, which suggests the marriage between himself and Eadgifu was a faithful and loving union. It cannot have been easy to reject her for another.

Harold had to live up to his duty of kingship, keeping his people safe. He organized his armies and lined his shores in Sussex and Kent with men and naval forces. However, he miscalculated when he disbanded the fyrd in September because he thought that William would by that time have called off his invasion. He thought he was able to march north to fight his brother and Hardrada without leaving his lands properly defended – but how wrong he was. And when he heard after a hard-won victory against the Norwegians, that William had landed in Pevensey and was ravaging his lands, he had to abandon his plans to reorganise the militia in York and divi up the booty they had taken from the defeated Vikings to march south and face William at Hastings within a few weeks.

No doubt all this would have an effect on his mind and body and may have upset his decision-making processes.

It is a myth to think that the same body of army was the one that went up to Stamford Bridge and back to London. The elite huscarls – his personal bodyguard – would have likely to have been with him forward and back, as long as they were not too badly wounded from Stamford. But the fyrd that came back down could have been a mixture of the fyrd that went up from the lands close to the south, especially the men of Sussex whose lands were being plundered, were likely to have been a new army gathered from the counties that had not been called to York.

Even so, the long march and the long day’s battle would have meant that they were weary, and their desperation to finish the battle may had led some of the more undisciplined men to leave their lines and run down the hill to their deaths at the hands of William’s chevaliers, his mounted horsemen.

One last parallel I can see is that both kings were defeated and died violent deaths – Harold in battle and Charles I on the scaffold – which were followed by dramatic regime change. Despite that some things endured. What was the greatest legacy Harold left England, in your opinion?

I think probably his greatest legacy was not as king, for he failed miserably there, not that he didn’t try heroically and most of what he did that day I cannot fault, but that aside, he put an end to the Welsh incursion into England, the raids, the stealing of cattle and humans for slaves, and the devastation they caused for a long time by decisively defeating the Welsh with the help of his brother, Tostig. Unlike the Normans, he didn’t try to conquer the Welsh but rather he diminished their power, and he did this by getting the Welsh to kill their King Gruffudd, who in actual fact had a lot of enemies in Wales. With their figurehead dead, Harold was able to get them to submit and Gruffudd’s brothers were allowed to take over Wales in Gruffudd’s stead.

Of course, this meant that the Normans found them easier foe to deal with than if Gruffudd had remained in power.

Finally, the civil wars have been well represented in reenactment for decades, but Anglo-Saxon reenactment is most definitely a thing too! How have you found being a reenactor of the period has shaped or changed your view of the period?

Reenactment is more about experimental archaeology and very useful for writing the novels I have written and am still writing. I think it has been researching the sources that have changed my view more than reenactment, but I do try to think what can my writing bring to reenactment as well as what can I learn from reenactment.

This has been fascinating, seeing parallels and differences between the two kings and their times. Thank you for sharing your thoughts!

Thank you for having me on your blog, Eleanor. I have really enjoyed seeing my period of interest and my king in the contexts that you have given me. It’s really interesting to compare historical eras, and actually, there isn’t a lot of difference when it comes down to it. Same problems, different times.

***************************************

Paula was born in the ancient Saxon County of Middlesex in 1961. She grew up in Australia, hearing stories from her dad about her homeland and its history. As a youngster, she read books by Rosemary Sutcliff and Leon Garfield and her love of English history grew. At 16, her family decided to travel back to England and resettle. She was able to visit the places she’d dreamt about as a child, bringing the stories of her childhood to life. It wasn’t until later in life that Paula realised her dream to write and publish her own books. Her debut historical novel , Sons of the Wolf, was first published in 2012 and then revised and republished in 2016 along with the sequel, The Wolf Banner, in 2017. The third in the series, Wolf’s Bane, will be ready for publishing later this year.

In the midst of all this, Paula has recently had her book, Searching for the Last Anglo-Saxon King, Harold Godwinson, England’s Golden Warrior published with Pen and Sword Books and is working on a biographic of King Edmund Ironside for them. She has also written a short essay about Edmund for Iain Dale’s Kings and Queens, as well as articles for historical magazines. When she is not writing, she is a psychiatric nurse, mother of three grown up kids and grandmother of two and also reenacts the Anglo-Saxon/Viking period with the awesome Regia Anglorum. You can find her on Instagram, Facebook, Threads, X(Twitter), Bluesky, and her own Website.

The title image is a fragment of the Bayeux Tapestry showing Harold as he comes to Normandy to inform William he is the successor of King Edward – via Wikimedia.

Thanks for hosting me Eleanor! It was such fun answering your questions.

LikeLiked by 1 person