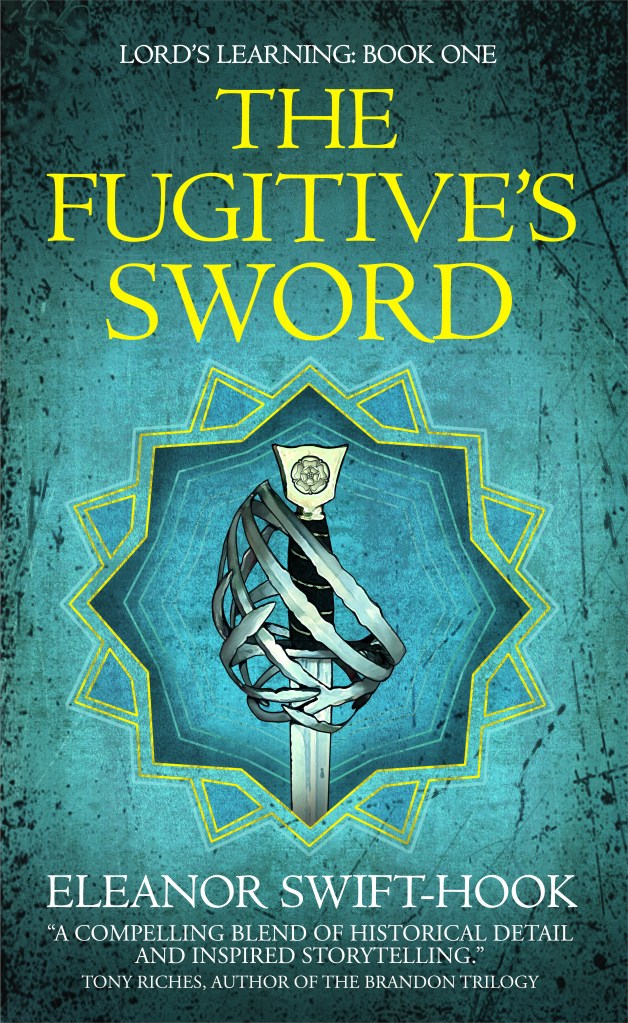

The Fugitive’s Sword is now available as an audiobook!

When I was looking into having The Fugitive’s Sword made into an audiobook, I knew it needed a narrator who was sympathetic to the period and that was a pretty big ask. So when I learned that Andrea Zuvich – better known on social media as ‘The 17th century Lady’ – was an audiobook narrator, it was very much a matter of serendipity! Andrea is a specialist in the Stuart era and has written several books about the Stuarts herself. She and her husband, Gavin, work as a team, narrating and producing audiobooks. She has done an amazing job on The Fugitive’s Sword, bringing it to life, so I was very keen to seize the opportunity to ask Andrea about her work on the book and how she approached it.

For most of us, audiobook production is an esoteric matter. Could I begin by asking you to share some brief insight into the kind of thing it involves? What are the most difficult aspects of audiobook production to get right? Do you have a routine for preparing to read?

Yes, many people are under the impression that narrating is the same as reading aloud, but it’s not. I read aloud to my daughter every night, but I don’t have to worry about my voice being crackly with a cold, or if I don’t pronounce something correctly. I can make mistakes, and it’s fine. But with audiobook narration, the microphone picks up everything, so we use a noise gate – which can often take out breaths, etc. It’s all very technical to me but my husband does the bulk of the work in the editing.

“It may seem as though a narrator simply reads a book, but no. I rehearse, research words and pronunciations, and we have to watch for mouth noises, etc, and the post production (editing, retakes) can be 3 times the time it takes to record.”

I rehearse the chapter aloud at least once before we record, but even then, mistakes can happen. If I mess up, I can repeat the line and this gets corrected by the editor/sound engineer. There is an initial edit session by Gavin, and then I listen to the whole track (chapter) and any pops or clicks in my speech, any mistakes in my reading, get flagged up and we do re-takes and then another listen through. An 8-hour audiobook is usually around 50 hours of work for us, all said and done.

Your audiobook narration is a performance art and you bring many elements to it. How did you develop those impressive performance skills?

Thank you very much! I’ve been drawn to performance for as long as I’ve wanted to be a historian – so since I was about six or so! I took a lot of drama, acting, foreign languages, choir, and TV & radio courses and I also performed in many plays and some films during my teens, and I had to use various accents and so I think that all helped.

You sing some of the songs! I know you are a singer of early modern pieces, were any of them songs you already knew? Did they take a lot of rehearsal? Which was your favourite of those you sung?

Yes, I love singing and it was a treat to be able to perform some Early Modern pieces during the course of the narration of this book. I don’t want to give anything away, but one of the main characters, Kate, sings a song, Mary Ambree, in a scene of great turmoil and it gets repeated later and I think it’s such a lovely melody and one that can stay in your head – in a good way! I didn’t know the Dutch song, so I had to look that one up and practice that one many times before recording it. It’s such fun to include songs!

I was particularly impressed by the way you were able to give each character their own voice. Do you read the character’s part in the book to yourself a few times before doing the official reading to better understand each one when bringing their voice to life, or do you find the voice suggests itself at first reading?

I read the book twice – the first time was a straightforward read to see what happens, the second time was with meticulous notes about age, place of origin, and any characterisation. I made a list of the characters and put their ages, social level, place of origin, etc. and that helps form my characterisation. I got in touch with you several times to ask your opinion and preference on things and I think it really helps to have communication with the author.

Did you do any research beyond the book to find out how specific characters might have spoken?

Yes, I like doing my research! I looked into alum, the Siege of Breda, and some words I was uncertain about with pronunciation. There are fantastic accounts on YouTube which have native speakers pronouncing words. This helped me out a lot.

Did you find you needed to get into character to read from their perspective and do you have a process for doing so?

Your characters are so well-described that I was able to form an idea of what they sounded like based on that and that helps the whole process. Sometimes an author leaves their characters vague and to perform that can be trickier without more detail. But before I record, if there are different characters in a given scene, I highlight the different characters with different colours so I remember which accent is which.

For me, the way you can so smoothly switch between voices in dialogue, usually with participants who have very different specific accents, was most impressive, what did you find most difficult when dealing with mixing accents in a single conversation?

Thanks! I’ve always loved accents – my parents are from Chile and my father worked as a translator for many years, and speaks nine languages, so I grew up listening to a wide variety of foreign languages and accents. The Spanish characters, in particular, were easiest for me as my Mother Tongue is Spanish, so I’ve grown up with accents like that. I’ve had experience with dialogue between characters from different countries – I gave myself a hard time in one scene of my own book, The Stuart Vampire, in which accents were used in a conversation involving several very different characters. For The Fugitive’s Sword, I had a similar challenge as I needed to up my game with the array of accents and characters, some characters not seen again until the end of the book, but I like a challenge and so I think that was most enjoyable for me.

Was your favourite character to voice the same as your favourite character in the story and what was it about each of them that led to you feeling that way?

I really liked Jorrit – and felt very protective of him. I saw him as a very young boy who has a very childlike voice in the beginning and I made a conscience decision to change his voice slightly as he goes through a variety of experiences that bring increasing maturity to him. As for the Schiavono, he reminded me of swashbuckling heroes from the Golden Age of Hollywood and characters like Percy in The Scarlet Pimpernel, so I envisaged him in that way and I always found him a fun character to voice.

Which character did you dislike most as an individual – did they present you with any challenges when voicing them as a result?

There are different unsavoury characters that turn up throughout the book, and it’s always fun to play a baddie. In terms of a specific character, I didn’t really like a certain Captain, which readers will probably understand. I tried to make his voice grow more menacing as the story unfolded – hopefully I managed to do that!

What did you most enjoy about working on The Fugitive’s Sword?

It’s such a thrill to work on a story set in the seventeenth century – you know how much I adore that period. It’s also wonderful to be able to bring to life this work by an author who is so beloved by readers and colleagues alike. I really hope listeners enjoy the audiobook. Thank you for this opportunity!

Thank you so much for drawing back the curtain on how you went about bringing The Fugitive’s Sword to life. I am so happy to be able to share your wonderful production of the book with all those who already love following Philip Lord’s adventures, and with those who are audiobook fans and will come to discover him through this.

The Fugitive’s Sword is now available as an audiobook through Audible. It is narrated by Andrea Zuvich, produced by Gavin Orland, cover designed by Ian Bristow, and theme music composed and performed by Earth Forge.

A seventeenth-century historian and author in her own right, Andrea Zuvich also has more than a decade of acting experience, performing such roles as Queen Gertrude in Hamlet, Isabella in The Spanish Tragedy, Hermia in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Frenchy in Grease, and Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire, among others. She has appeared on the BBC, NBC, NTR and other networks and narrated several books in a wide variety of genres, including Eat Like a Local: Malaga Spain Food Guide (2022), Her Perfect Scoundrel (2022), So Little Done: The Testament of a Serial Killer (2023), and The Apprentice: Love and Scandal in the Kingdom of Naples (2023). She has also voiced media for several mobile apps and is a singer of early music and opera. Andrea is author of several books on the period including ‘Sex and Sexuality in Stuart Britain‘ and Ravenous: A Life of Barbara Villiers, Charles II’s Most Infamous Mistress. Host of ‘Stuart Saturday Live‘, and a co-founder (with Dr Erica Canela and Mark Turnbull) of the Stuart History Festival, the world’s first-ever in-person festival dedicated to Stuart history.

Finally, if you enjoyed the theme music, you might like to hear the full piece of music from which it is taken, The Shadow of Treason, illustrated on YouTube with paintings depicting characters and events from Lord’s Learning and Lord’s Legacy.