Historical Background to The Devil’s Command

Unlike the previous books in this series, many characters in The Devil’s Command have famous historical antecedents.

Amongst others, we meet King Charles himself, his nephews Prince Rupert and Maurice, the Earl of Essex, Lord Brooke, Lord Digby and Boye the dog. I have done my best to place them approximately where and when they were as we encounter them in this story, but not invariably so. Rarely, some of their words are taken in part from the historical record, but most are purely my invention. Their attitudes and personalities are my interpretation taken from what I have read about them.

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The battle of Edgehill was the first battle of the English civil war. It took place pretty much as I have described, from the initial encounter of some of Prince Rupert’s foragers with their Parliamentarian opposite numbers the evening before. Although inevitably, as we ride with Gideon, I only show a narrow slice of what was a highly complex event as all battles are.

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © David Stowell – geograph.org.uk/p/37614

The terrible treatment of the Parliamentarian baggage train by Digby’s horse is sadly historical but it was far from the worst atrocity that would be meted out on the non-combatants following each army in a war that became ever more brutal as time went on. That unwelcome accolade must surely go to the massacre and mutilation of Royalist camp followers, mostly women with their children, by the cavalry of the New Model Army after the Battle of Naseby in 1644. A deed that was then celebrated in the London press as being a worthy and righteous act.

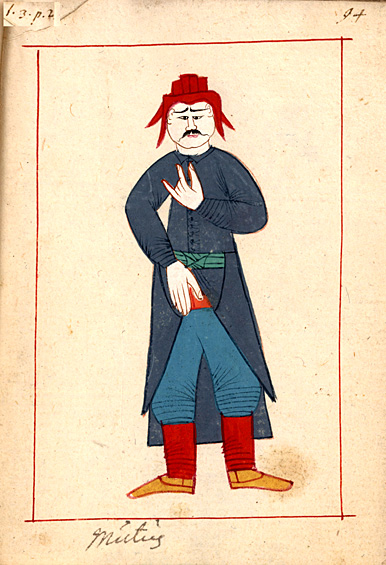

One other thing worthy of mention here is sign language. There is much evidence to suggest local sign languages of a simple finger spelling variety had been known from mediaeval times at least. But there was a cultural flourishing of one particular sign language at the Ottoman court in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with many hearing people learning it including the sultans themselves.

In 1605, Henry de Beauveau, the French soldier and diplomat who visited the Sublime Porte escorting the French Ambassador, said this was called ixarette, probably a French pronunciation for işaret the Turkish word for ‘sign’. Later accounts suggested that this language could be used to hold sophisticated exchanges suggesting it was indeed a language in its own right and not just alphabetic finger counting.

Claes Rålamb, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Finally, a word about marriage in this era.

At this time the strict legal formalities around marriage had yet to be set in stone as they were eventually in the 1753 Clandestine Marriage Act. A wedding licence or banns to be read and a church service, whilst vital where money and property rights depended on the marriage being legally indisputable, were not technically necessary. Marriage was not a sacrament. In law, to marry all that was required was a spousal. At its most basic this was simply to declare, in the present tense, that you accepted the other as your spouse (the ‘I do’ of the marriage service). That such spousals occurred is shown by the amount of analysis given to the validity of various wordings used in such marriages by Henry Swinburne the ecclesiastical lawyer in his work on the subject written in the 1620s. However, in the Caroline era until their suspension in 1640, the ecclesiastical courts dealt with very few cases, suggesting that they were rare.